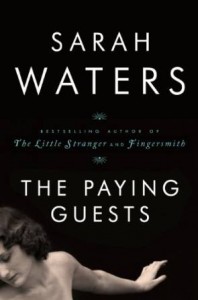

Like most readers, if I thoroughly enjoy an author’s work, I am usually keen to read their subsequent novels. Because I was engrossed in The Little Stranger, which I read it a few years ago, it was with that particular anticipatory glee that I cracked open The Paying Guests. Sarah Waters writes comfortable, homey stories with very adept description making the reader at home in the parlor with her characters. You almost feel as if it is you who dropped round for tea, or came clamoring to the front doorstep having just heard the news- whatever that news may be. She writes of families and groups where you have the odd sensation of feeling you are one of them. It seems so natural and so friendly; I would not hasten to call it a device. Is it not the goal of any story to draw you in? This she manages with alarming dexterity. At first, a sleepy house in a fine neighborhood inhabited by a widow and her unmarried daughter would not inspire most readers to pick this up, unless you happen to be a certain type who absolutely loves this kind of cozy British drama. That was all the impetus I needed.

It would take more than tea and biscuits to keep the story going. When we learn that the two women are to take in boarders, I was prepared to read about all sorts of petty conflicts, judgments and disapproval cropping up everywhere, but that alone would not have been enough either. What keeps the story moving very quickly through 564 pages, is a knack for getting the reader more and more deeply involved. In The Little Stranger, the author had the same effect on me. The tale got darker, the characters in much greater peril, the family in more trouble, until I simply had to know what had brought them so far off course. In both books, it is as if the reader starts at the top of a staircase and then just keeps going consistently down, until you fear for these characters so much that you cannot close the book and go to sleep. They all set out innocently enough, with good food in their bellies, good clothes on their backs, good values and intentions all in place, their standing in good order, but piece by piece, it starts to go south and then keeps right on going. You begin to fear that they are associating with the wrong sort, as they would say in England, and that they are in danger of getting in over their heads. Disgrace, scandal, and being the object of gossip, all being a fate to be avoided at all costs, seems to dog Waters’ characters from start to finish. Reading this book brought me back to the days when I would sit in my grandmother’s living room hearing her recount various stories of people she had known, who seemingly through no fault of their own, had gotten mixed up with someone who had done nothing but drag her friend down, and may be leading them to a bad end. You hear these stories, and you file them somewhere in your mind, not to resurface until you dive into a tale like The Paying Guests, and it all comes back. The warnings were there… but she deliberately went back… and why she wouldn’t listen… and on and on until the unfortunate circumstance can no longer be changed. It is for this reason that Water’s novels become thrillers, although they would not be categorized as such.

As I usually read reviews of books after I have finished them and have formed my own opinions, I was happy to learn that others agreed with my assessment.

“Brings to mind the dark and ominous atmosphere of Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca. . . . Waters’ skillful mastery of detail and atmosphere brings the suspenseful tale to life.”

—Winnipeg Free Press

“Waters is so confident – and, line by line, her writing so beautiful, precise and polished – that she sweeps all before her. . . . [I was] helplessly pulled along by the magnetic storytelling. Twice in the last few pages I shouted aloud – though whether in joy or horror I will not tell you. Sarah Waters skilfully keeps you guessing to the end.”

—Tracy Chevalier, in The Guardian

“Waters’s page-turning prose conceals great subtlety. Acutely sensitive to social nuance, she keeps us constantly alert to the pain and passion churning under the “false, bright” surface of gentility. From a novelist who has been shortlisted for the Booker three times, this is a winner.”

—Intelligent Life magazine (The Economist)

The weather is delightful these days here at Windy Bay. Last Sunday, I lounged on our floating dock in a comfortable chair, getting up from time to time for a swim, and thought that I was actually in “beach read” mode. Reading hour after hour, on a beautiful afternoon, with no thoughts of putting the book down until I reached the end, is my idea of heaven. If it were a rainy afternoon, I would have had the kettle on and be every bit as deliriously happy. A good story teller will have that effect.