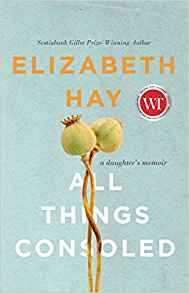

To examine Elizabeth Hay’s wonderful book called All Things Consoled is to gaze at the nature of the word itself. Anyone facing grief, or dealing with the difficulties of aging parents, or struggling with the reconciliation of old beefs, and the nature of letting go, will understand that grief is massively challenging. Caring friends may ask us how we are progressing. We will always come up blank. We can try to find peace, to achieve closure, to move on in our lives, but just when we feel we are making some headway, the past circles back, and there we are crying in the car when a sad song comes on the radio. We don’t get over things. At least, that is my experience. As I learned on the long canoe trips of my youth, the pack you portage gets a little lighter every day. That best describes my progress or lack thereof.

All Things Consoled, reads like a diary of the journey. It felt as if I was in her family with her, and I could see it all as clear as a bell. It is the great joy of my life to have so many experiences, so many connections, and so many travels all taking place within the bounds of my quite elastic imagination. A recent class with Margaret Atwood asked me to consider how to evoke emotions in the reader. Her statement landed like a direct hit. That is the trick of it.

Elizabeth Hay managed to evoke memories of all the irritating moments where you want to scream, but know that would be very unwise. By using her considerable skill to put me in her mother’s kitchen, I was transported back to the fifties when as a young girl, I experienced first hand, the holdover of the depression years, and the need not to waste food. Two characters, named willful and woeful were given little dishes covered in wax paper and then saran wrap before it found its cling, two measly bites that must be saved, less “Willful waste brings woeful want.” In my mother’s case, the sensibility only applied to food, a contradiction we often pointed out. Hay’s mother’s endearing obsession had me thinking back with great affection to my mother’s old pink fridge at our summer cottage on Lake Joseph in Ontario.

As for the father, although they were vastly different kinds of men, there were similarities there too. Punishment, as meted out to children in our time, could be harsh. Micheal Ondaatje in Warlight wrote that to write a memoir is to be an orphan. Surely there are great hurdles. One wants to get close to the truth, but one loathes to tell it. Idealize the whole family and write a rosy tale where all skeletons are swept dutifully under the carpet, does not come off as believable. To reveal all is sometimes too painful for anyone to read. How to get it just right must be the greatest challenge ever. It is not uncommon for some to write more than one memoir, because side stories and different issues keep popping up.

They will keep on coming too because the heart of the story, the telling of it, is a journey. In the case of All Things Consoled, the reader comes away with great respect for the author. She found the right note, and she managed to achieve a balance with her parent’s foibles and her own. We, too, can relate to their struggles and feel compassion for them as the frailty of old age crept in. Memorable characters, evocatively brought to light, makes this a great read.

From Page 233:

“The instinct to make art had abandoned her, but not the instinct to save food. She could not pass the communal fruit bowl in the lobby without her hand reaching out like a raccoon’s for apples and oranges, which she slipped into the basket of her walker and wheeled to her room. We took to calling her the fruit tree, self-grafting, everbearing. Her little fridge groaned with what she salted away. Every few days I emptied it into a canvas bag, assuring her that nothing would go to waste. Then I would stop by the kitchen on my way out of the building and put the food in the garbage and the napkins into the laundry bag and the plates on the counter. I stopped at the famous fruit bowl and returned apples and oranges.”

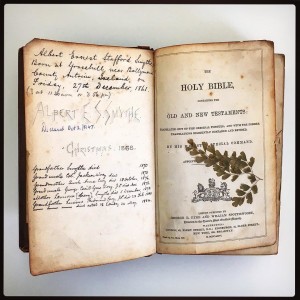

How this passage makes me anxious! I think of my parents with great affection at Christmas time. We were so lucky to not know real want, a fact my Mom pointed out constantly. Elizabeth Hay helped to console me, for I will always miss them. As we always gave books as gifts, and Boxing Day meant cracking open a great new read, with a personal inscription on the title page, I still have bits of them with me in my library. As for the living room, I have their console tables too.