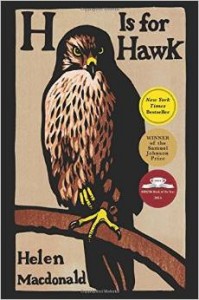

I first heard about H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald when I learned it was a number one bestseller in the United Kingdom. Not knowing much about falconry, I thought I would order the book and take a look. I was not prepared to be utterly stunned by Macdonald’s deft craftsmanship. Her powers of description kept stopping me in my tracks. I would read a page or two and then pause; it was as if I needed time to digest the imagery.

It is after the terrible and sudden loss of her father that Macdonald decides to tackle the enormous challenge of adopting and training the fierce and unruly goshawk. The bird of prey she names Mabel isn’t having any part of it at first. What drew me into the story was the battle between a wild creature’s desire to be free, and a woman hurting and alone who accepts the challenge unflinchingly. Turning to the writing of T.H.White’s who in The Goshawk, describes his own triumphs and defeats, we learn about the level of patience the practice of falconry demands. Macdonald’s father taught her to be patient, and in accepting the challenge of taming Mabel, it is as if she has something to prove. It is her desire to show her father that she had not forgotten either his lessons, or the man himself, that drives her and compels her to persevere in the face of many cuts, bruises, frights and frustration. I imagine anyone in the throws of grief attempts to describe the experience, but I am at a loss to recall anyone as capable of getting to all the nuances better than Helen Macdonald.

“And it wasn’t until we were standing on Queenstown Road Station, on an unfamiliar platform under a white wooden canopy, wasn’t until we were walking towards the exit, that I realized, for the first time, that I would never see my father again.

Ever. I stopped dead. And I shouted. I called out loud for him. Dad. And then the word No came out in one long, collapsing howl. My brother and my mother put their arms around me, and I them. Brute fact. I would never speak to him again. I would never see him again. We clung to each other crying for Dad, the man we loved, the quiet man in a suit with a camera on his shoulder, who had set out each day in search of things that were new, who had captured the courses of the stars and storms and streets and politicians, who had stopped time by making pictures of the movings of the world. My father, who had gone out to photograph storm-damaged buildings in Battersea, on that night when the world had visited him with damage and his heart had given way.” Page 106

There are aspects of Mabel’s moods that mirror the wild panic grief can impose.

On the back jacket sleeve of H is for Hawk I read that Helen Macdonald is “a writer, poet, illustrator, historian, naturalist, and an affiliated research scholar at the department of history and philosophy of science at the University of Cambridge.

Macdonald uses her poet’s skill, combined with her naturalist’s eye to craft passages of the most beautiful description I have read in years.

“It’s turned cold: cold so that saucers of ice lie in the mud, blank and crazed as antique porcelain. Cold so the hedges are alive with Baltic blackbirds; so cold that each breath hangs like parceled sea fog in the air. The blue sky rings with it, and the bell on Mabel’s tail is dimmed with condensation. Cold, cold, cold. My feet crack the ice in the mud as I trudge uphill. And because the squeaks and grinding harmonics of fracturing ice sound to Mabel like a wounded animal, every step I take is met with a convulsive clench of her toes. Where the world isn’t white with frost, it’s stripped green and brown in strong sunlight, so the land is particoloured and snapping backward to dawn and forwards to dusk. The days now are a bare six hours long.” Pge 242

Our house on Lake Coeur d’ Alene is a lofty perch from which we view an endless array of hawks, ravens, eagles and osprey. They are mesmerizing. A visiting friend whose conversation had drifted off as he watched a circling hawk asked me this question: “How do you get anything done?”

“I don’t,” I answered.

This week the whole world has been sickened by the death of a favored lion named Cecil. More ghastly pictures come across our screen. The President of the United States has stated that something must be done about climate change. We can no longer do nothing while the delicate balance of our beautiful world is disrupted. The west is burning up. The Cape Horn Fire in Bayview, Idaho, a place I revere, ravaged swaths of a mountain forest. The scarred woods are eerily quiet. Even the yellow jackets have moved on. We are not aware of the gentle cacophony of life until we stand in the wasteland. We need our poets more now than ever. We need naturalists and writer’s who can give voice to our plight. H is for Hawk is much more than a pleasant summer interlude; it is a screech in a particular moment in time.