In the fifties, we had our milk delivered daily. It came in quart-size glass bottles with a pint of cream on the side. There was a little cabinet on our back porch with two doors. Our delivery man opened the small cupboard, gathered the empties which had been washed by my mother, looked for instructions which may have requested either more or less, depending on the time of year, and then placed our milk in its little home and went on to the next house. It was often my job to open the other side, housed as it was in the laundry room, and put the bottles in the fridge. Gifted with a crazy imagination, I went through the small opening, trying to prove that a skinny milkman could rob us blind if that were his intention. Everyone would scoff at my fears because a milkman was always in a position of trust.

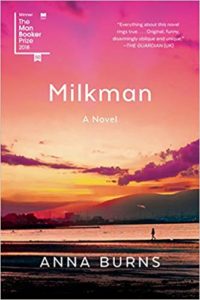

We learn in the opening pages of Anna Burn’s Man Booker Prize-winning book, named Milkman, that this is not a cozy tale redolent of all things shiny and secure as we now tend to think about the fifties. This book is set in Northern Ireland in the seventies at the height of what is usually referred to as the troubles, and the milkman was probably not a milkman at all, but a para-military, sinister figure, stalking the narrator.

“The day Somebody McSomebody put a gun to my breast and called me a cat and threatened to shoot me was the same day the milkman died. He had been shot by one of the state hit squads, and I did not care about the shooting of this man.” Page 1.

Kwame Anthony Appiah, chair of the Booker Prize judging panel, put it this way: “From the opening page her words pull us into the daily violence of her world- threats of murder, people killed by state hit squads- while responding to the everyday realities of her life as a young woman.”

The protagonist, recipient of not only the threat, from Somebody McSomebody but judgments and warnings from the rest of the community went mysteriously, unnamed. Her family is as well, and we distinguish them, one from another, through their place in the grand scheme of things. She is known as “middle sister.” To the best of my knowledge, this is a first. What fills me with enormous curiosity are these two questions: why did she choose to tell the story this way, and how was she not talked out of it?

The book is not given to explanations. The troubles, the author assumes are well-known to everyone and need no history lesson. The same goes for geography, and the nature of the conflict, the violence and mistrust everywhere in the community. People from “over the water,” or “over the border” or “over the road” are the anchors we understand. She never writes of England, or Great Britain, or Ireland or the west. Instead, she chose to write of the state, of the resisters to the state, to organizers and suspected para-military. It gives the setting a surreal, other-worldly aspect. There is something fantastical in the tale that I clumsily struggle to define. By using these devices, leaving names, and place names vague and untethered, we are forced to work a bit harder to find our own place for them. The heart of the matter becomes more prevalent because denied our judgments and bigotry; we must begin anew. The conflict starts to feel everlasting. If you consider that the Anglo-Norman claim to the Pale, the strip of land under their rule, goes back to 1169, one can only imagine what a tangled web, woven over hundreds and hundreds of years can succeed at all. How does one distinguish the occupiers from the occupied when they all look the same?

“Every resident was supposed to know what was permitted based on what was not permitted.” page 24.

“There was the fact that you created a political statement everywhere you went, and with everything you did, even if you didn’t want to.” Page 25

One can imagine the tension facing mothers in the midst of the era where it all started coming to a head. Sons disappeared and took up arms: daughters must be married, safely and quickly and into the right religion. Occupiers must prove they are superior, which has come down as the ultimate justification for the plantations of the seventeenth century. The occupied fight this concept at every turn, and therein lies the trouble. Stubborn determination, bred in the bone, allows citizens to maintain who they are, no matter what happens. That is the crux of the issue and the territory the protagonist must negotiate. Wearily, putting the book down late at night, I would think, what are her chances?

I know I am a rare bird regarding my love of stream of consciousness writing. When done well, it takes my breath away. I also understand why professors, editors, and publishers may be less fond, but the very best of it is astonishing.

Depression would seem endemic, but the mother speaking of her husband said, “I never understood your father. When all was said and done, daughter, what had he got to be psychological about?” Page 81

Burns answers the question in very characteristic and mind-boggling style.

“She meant depressions, for da had had then: big, massive, scudding, whopping, black-cloud, infectious, crow, raven, jackdaw, coffin-upon-coffin, catacomb-upon-catacomb, skeletons-upon-skulls-upon-bones crawling along to the grave type of depression.” Page 85

That is a far cry from Winston Churchill’s black dog. The habit of heaping description- upon-description remained consistent throughout. As always, it is up to the reader to decide if this sits well with them or not. With so many books coming out every year, with so many favorite authors from whom to choose, with endless topics and settings, we owe a debt to the judges and the publishers and the editors who find strokes of genius in a great unfolding succession. Milkman was the first choice of 2019 for The Best Food Ever Book Club which has plumbed the depths of the long-list and the short-list lo these three decades we have been reading together. We never even scratch the surface of all the great literature waiting for us to ingest. Where will we go from here?

Milkman was quite beyond the pale.